From Virginia Business By STEPHENIE OVERMAN

‘Founder-focused’ accelerators boost startups

Capital One’s Richmond-based Grow@1717 accelerator program aims to meet the need of “Main Street, mom-and-pop” startups, says Toria Edmonds Howell, engagement manager at the bank’s Michael Wassmer Innovation Center. Photo by Matthew R.O. Brown

Virginia’s version of the business accelerator doesn’t always rely on the traditional model of sponsorship by angel investors who provide capital for startups, usually in exchange for convertible debt or ownership equity.

Here in the commonwealth, “it’s more founder-focused,” and accelerators are often run by nonprofit organizations, says Conaway Haskins, vice president for entrepreneurial ecosystems at Richmond-based Virginia Innovation Partnership Corp., a state government-related nonprofit that supports economic development-oriented Virginia-based startups through early-stage seed funding and other efforts. “There’s not as close a tie-in to investors.”

The reason for that may be that Virginia innovators who were involved with typical Silicon Valley-style accelerators had mixed experiences, Haskins says. These accelerators generally provide funding in exchange for equity in the company.

The Virginia approach, he says, generally allows startups to go through the intensive accelerator process “without investment being so much of a carrot.”

For the 12-month period ending June 30, 2022, VIPC provided about $960,000 in grants to support programming and operations at about a dozen accelerators, incubators and innovation hubs around Virginia. (Formerly known as the Center for Innovative Technology, VIPC also offers direct support for select startups through its commercialization and investment divisions.)

The accelerator experience can be intense for entrepreneurs, filled with scheduled classes, mentoring and peer-review sessions, with programs often running as long as 12 weeks.

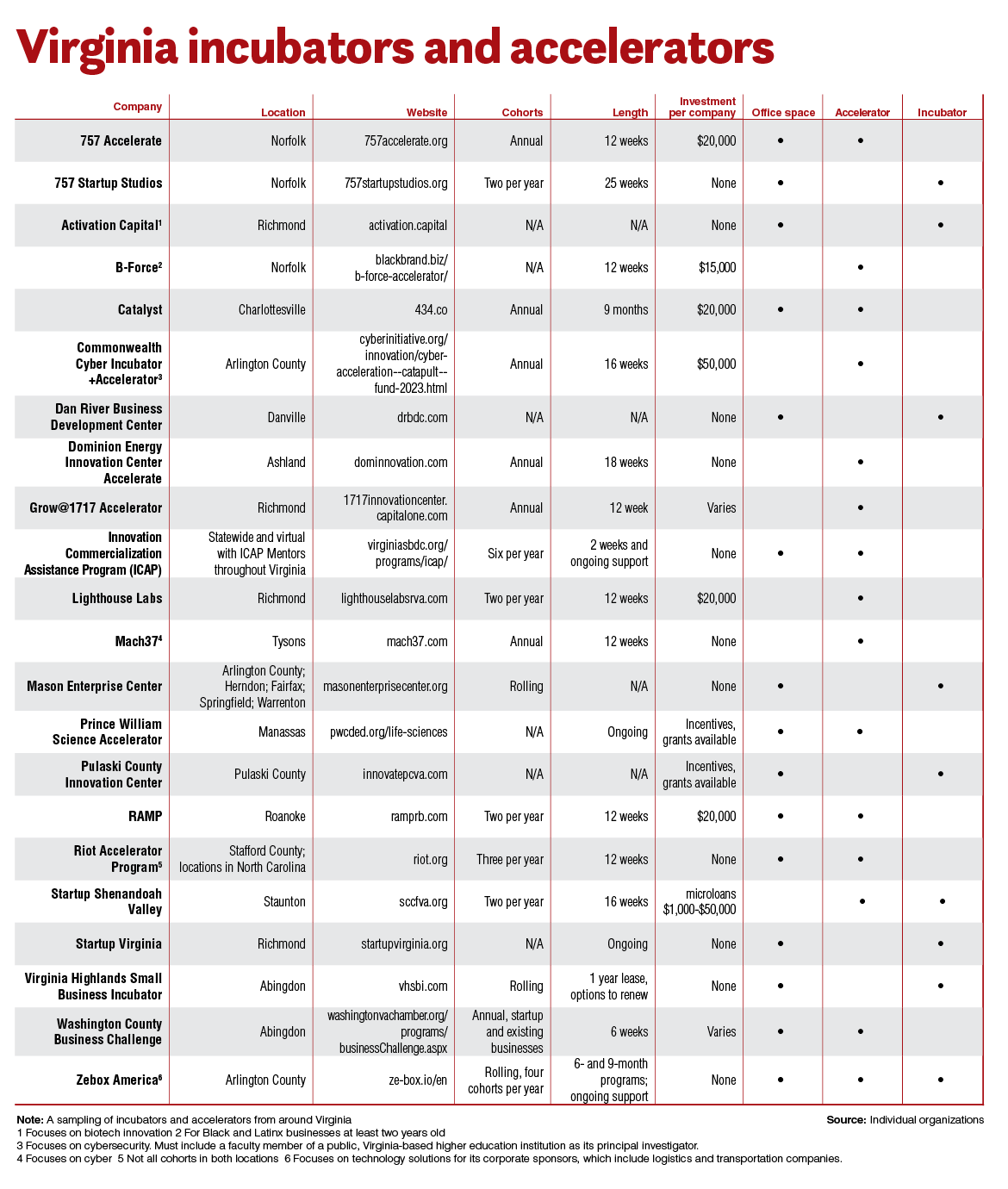

Small business owners sometimes graduate from business accelerators to incubators, which typically provide long-term assistance, including office space. Some organizations, such as 757 Collab in Norfolk, run both accelerators and incubators or hybrid programs.

While accelerators and incubators are often associated with high-tech startups, their Virginia counterparts often offer programs tailored for a wider variety of industries, though some may target a particular sector that needs development assistance locally or statewide, Haskins says.

‘Mom-and-pop businesses’

That type of industry-focused approach is on display at Capital One Financial Corp.’s Richmond-based Grow@1717 accelerator program, located within the bank’s Michael Wassmer Innovation Center in the city’s Shockoe Bottom area. The nonprofit accelerator meets the needs of “Main Street, mom-and-pop businesses,” says Toria Edmonds-Howell, the center’s community engagement manager.

Grow@1717 launched as a pilot accelerator program in 2019. Two years later, the accelerator hosted a cohort of minority restaurant owners. In 2022, it focused on home-based child care providers, selected and funded in partnership with ChildSavers, a Richmond nonprofit that provides children’s mental health services and child care resources. Grow@1717 also has partnered with other organizations, including Lighthouse Labs, an equity-free, early-stage startup accelerator also based in Richmond.

“Child care is a hot topic coming off the pandemic,” says Edmonds-Howell. “When we wrapped up with the restaurant owners, there was an article [published about it] with a picture of an owner in her restaurant with her baby on her hip. That was an ‘aha’ moment for us.”

The child care program finished in November, with each of its seven participants receiving a $5,000 grant. To date, 19 small businesses have graduated from Grow@1717, and the accelerator has invested $145,000 in local small businesses and nonprofits.

DeShonda Jennings, owner of DJ Shining Stars Preschool in Chesterfield County, appreciates what she’s learned from Grow@1717’s free accelerator. She used the $5,000 grant her business received to make improvements to her facilities. “They taught us how to work on our business, not just in our business,” she says.

Grow@1717 plans to host another cohort this fall, but hasn’t decided on its focus, says Edmonds-Howell. “If it’s like in the past, there will be an ‘aha’ moment.”

About a 90-minute drive south from Richmond in Norfolk, 757 Accelerate also works on a focused model, seeking to aid “underrepresented founders,” explains Executive Director Evans McMillion. “We’re trying to remove barriers — not just financial barriers — for women, people of color and military veterans.”

757 Accelerate is part of 757 Collab, a nonprofit innovation network that also supports startups through its 757 Angels investment arm and its 757 Startup Studios incubator program. Participation in all 757 Collab programs is free.

Since 2018, 757 Accelerate has hosted five cohorts, with participants from 32 companies that have created more than 450 jobs. Accelerator participants receive $20,000 in seed capital without having to relinquish equity.

Following 12 weeks of training in a variety of topics, ranging from legal issues to marketing, investment pitches and more, each accelerator session concludes with an investor roadshow. Founders travel by bus along the mid-Atlantic to pitch their business ideas to angel investors. “It’s very competitive,” McMillion says.

Meanwhile, 757 Collab’s incubator counterpart, Startup Studios, has helped more than 70 early-stage entrepreneurs since its 2021 establishment in downtown Norfolk. Participating founders receive six months of free office rent, vendor discounts and access to mentors as well as programming on topics like those offered through 757 Accelerate, says Startup Studios Program Manager Hunter Walsh.

Mach speed

Initially, Mach37 in Tysons looked a lot like a tech-focused Silicon Valley-style accelerator, but its scope has expanded.

Created in 2013 with state funding as a division of the Center for Innovative Technology, which in 2021 rebranded as VIPC, Mach37 is now owned and operated by VentureScope, a Tysons-based consulting and venture investment company. Mach37’s name refers to “escape velocity,” the minimum velocity needed to escape earth’s gravitational field, mirroring the notion of what it takes for a small business to launch successfully.

Mach37 was created with a goal “to grow the next generation of cybersecurity [companies],” says Mach37 Executive Director and CEO Jason Chen, who’s also VentureScope’s CEO. And Mach37 has launched more than 70 cybersecurity companies, Chen says, but now, “we’ve opened the aperture,” and have expanded the accelerator’s scope to a more diverse range of tech companies, with more emphasis on artificial intelligence.

Jennifer Addie, Mach37’s chief operating officer and strategy director, says the accelerator has been looking “at what’s going to be on the horizon in space, satellites, deep fakes — things where they wouldn’t think of themselves as a cybersecurity company.”

The accelerator’s 90-day program emphasizes validating product ideas and developing relationships that produce an early customer base and investment capital. “Workshops are meant to fill gaps in skill sets or answer business model questions or develop solutions,” Chen says. “The answers are in the market. We want to give them time to go into the market.”

Mach37 does not charge cash to participate but has an equity fee, which is typical of the venture capital model.

Virtual acceleration

Many business accelerators and incubators are based in large cities, but Haskins notes that the pandemic has expanded the field. With virtual programming proliferating, organizations are increasingly able to reach startups in rural and remote areas, but local organizations also are being proactive by building entrepreneurial ecosystems in small towns and rural localities.

For instance, Shenandoah Community Capital Fund in Staunton offers Startup Shenandoah Valley (S2V), which aids entrepreneurs in the valley region from Winchester to Buena Vista. It’s a largely virtual accelerator but includes some in-person meetups and leadership coaching sessions, says Katie Overfield-Zook, entrepreneurial ecosystem builder for SCCF.

SCCF also has an incubator program in the works, which will be piloted in the second half of this year, says Anika Horn, the fund’s director of marketing and ecosystem building.

Since SCCF launched S2V in 2021, it has had five cohorts, with 40 business owners. Businesses have ranged from a cybersecurity business to a candle manufacturer to a plastic refabrication enterprise. There is a $1,000 fee. Participants work with coaches, mentors and peers.

“Peer-to-peer support is a lot of times their favorite part,” Overfield-Zook adds. “These are other people who have been in the trenches.”

In Abingdon, Virginia Highlands Small Business Incubator offers a physical site with 40 rentable office spaces, manufacturing pods, training and conference rooms, says Executive Director Cathy Lowe. About 30 of those spaces are rented by startups, transitioning companies and organizations with a tech focus. Current tenants include a microscope sales and service company, a book publisher, a financial advising group and a Virginia Highlands Community College welding class.

VHSBI also covers a lot of territory through its free Noon Knowledge training video series, which it posts to YouTube. Marketing and accounting trainings are especially popular.

“Social media has changed since 2014, so we have to keep updating classes,” Lowe says. “We keep evolving. If someone has a need, we do it.”